Use Computer to Solve Puzzle: SCUMM Games

I’m eschewing my normal review format for the first in what—hopefully—will be the first part in a series of blog/review hybrids about some of the video game based puzzle game experiences I’ve played through. To kick things off: SCUMM1“Script Creation Utility for Maniac Mansion”, the engine created by Lucasfilm Games that ran a lot of those early Point and Click adventure games. and SCUMM-like games.

Despite being somebody who had a strong interest in puzzles and riddles even as a child, I managed to more or less miss the big point-and-click adventure game boon of the late 80’s / early 1990s. I played a few here and there, Star Trek: 25th Anniversary and Leisure Suit Larry (at a friend’s house when his folks weren’t around 😅) leap to mind, but never really got a chance to play any of the Lucasfilm Games that were so popular during the era.

That lack of experience explains how I stumbled ass backwards into the genre a few years ago, when I played through Thimbleweed Park. It looked like a fun riff on The X-Files, had good reviews, and I was curious to try out a game that was released with a verb-object command system in two-thousand-seventeen. I picked it up in a Steam sale and—surprisingly given my peccadillo for buying games for cheap on Steam and never playing them— played it a month later. The game was a delight! Super fun, good puzzles, a fantastic sense of humor, and strangely addictive.

The game is broken up into nine, roughly 90-minutes parts, each focusing on a single character. I played it over the course of five days, playing a couple of parts each day. I noticed as I was playing, that there were jokes and references that I was clearly missing out on. It didn’t make the game any less enjoyable, but it did prompt me to look more into the history of the game. That’s when I found out that this game was a spiritual successor and love letter to the old Lucasfilm adventure games of old, made by the very same creators—Ron Gilbert and Gary Winnick—who kicked off that golden age with Maniac Mansion. (I write that like it was an important archaeological discovery and not, you know, the whole point of its very successful Kickstarter 😅) I had started at the end and while it was certainly enjoyable, there was a lot of context I was missing. The closest comparison I can make is that it would be to watching Serenity without having seen Firefly, enjoyable but you’re not getting the whole experience. The game was such a good time, and I’d heard so many good things over the years about those old Lucasfilm Games, that I decided to go back and start at the beginning. After finishing Thimbleweed Park, I immediately went out and picked up both games in the Maniac Mansion franchise and all four (at the time) games in the Monkey Island franchise.

For a 37-year old game, Maniac Mansion‘s scope and ambition is incredibly impressive. (Even more so when you consider that it originally had to fit on a floppy disk!) I’d expected it to be a fairly linear puzzle game, one that would either be too esoteric to be enjoyable in today’s age or so easy that I could get through it in a sitting. While it did have its esoteric moments—most of which were in the service of comedy, but a few of which were genuinely frustrating—it remains generally a pretty solvable game on its own, though one that I had to lookup some hints to get through. My playthrough took a little over six hours, which felt just about right.

The game also has something that many adventure games do not: replayability. There are seven different characters to choose from (you can pick three for each playthrough) and each character has their own special skills and talents, which changes which puzzles you can solve and how to solve them. I really like this approach, as it allows the game’s experience to feel somewhat unique to the person playing it. There are thirty combinations of characters you can play as and most groupings will require a unique combination of puzzles to solve. As a result, these unique pairs means there are multiple ways to beat the game and multiple endings. Also unusual is how important timing is. The game features scripted events that happen at certain points and knowing when these events happen and the ramifications of what they mean is crucial for being able to solve the game. The timed events and multiple endings are all the more impressive considering the limitations of the medium and genre at that time, great stuff!

I also really enjoyed the B-Movie Horror setting and narrative which seemed to take all those cheesy, low-budget movies from the 1950’s – 1980’s and throw them all in a giant blender. We’ve got mummies, delinquents, mad scientists, tentacles from outer space, nuclear reactors, sentient meteorites, and cars with fins, among many other references. The sense of humor and subject matter remind me a lot of Mystery Science Theater 3000, which maybe not-so-coincidentally debuted the year after this came out.

Being that the game is from the late-80’s, there are still some puzzle design elements that haven’t aged well. The most egregious for me are the dead ends in the games, states where you can no longer win the game, but the game doesn’t alert you to this fact. Modern games will either be setup in a way that doesn’t allow for a dead end (Thimbleweed Park, for example, did this very well) or will give you a Game Over screen when you reach that point. As someone who is now in their 40’s, I’ve found that my tolerance for games that don’t respect my time has greatly diminished, and so I bristle at the absence of these modern creature comforts.

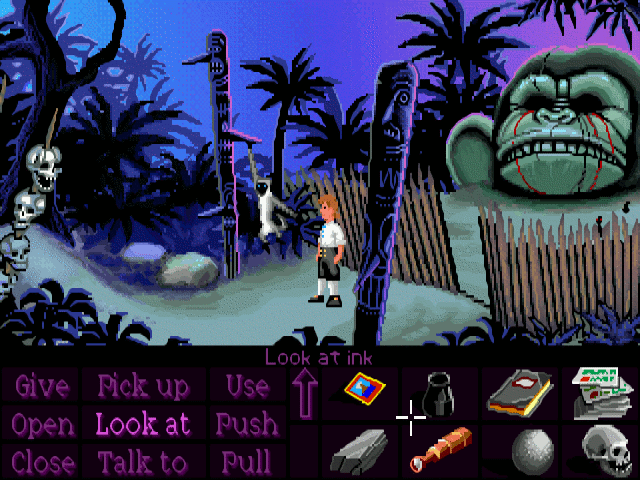

Maniac Mansion, of course, was incredibly influential, inspiring a golden age of point and click adventure games that would continue until a certain MYSTery game ushered in the CD-ROM era of FMV games with pre-rendered environments. While it wasn’t the first point-and-click adventure game, it was a revolutionary one; with its biggest legacy being the game engine that was created to run it: SCUMM. Creating a scripting engine to run the game was an incredibly forward-thinking idea, as it meant that porting the scripting engine to a new platform effectively ported any game written using that engine to the new platform as well. This led to over forty SCUMM titles being officially released over the next decade and countless fan projects in the decades since. It also helps that the SCUMM engine is really good, being both developer-friendly on the programming end and user-friendly on the execution end.

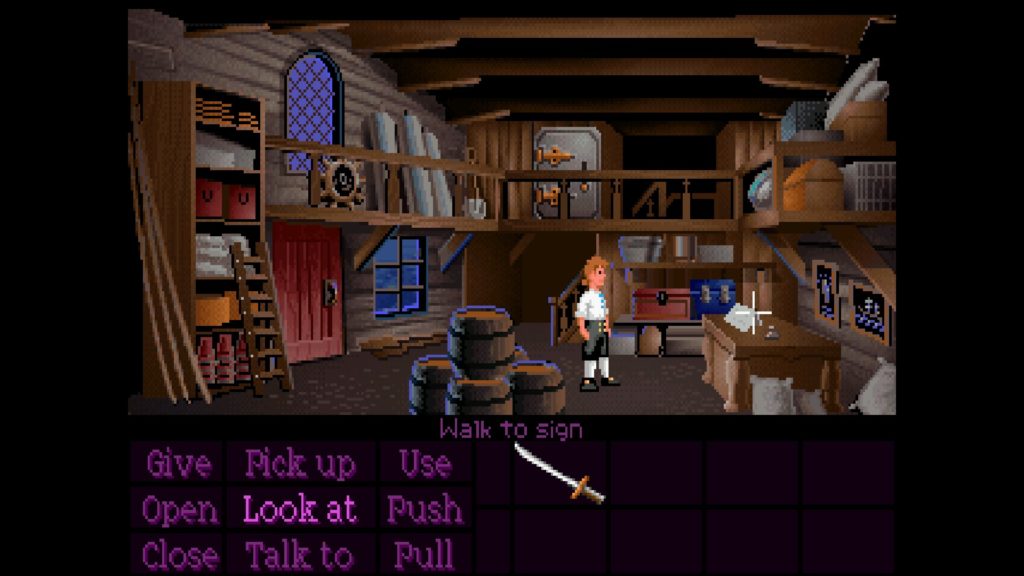

After playing Maniac Mansion, I decided to skip Day of the Tentacle for the time being and move onto The Secret of Monkey Island next. I picked up the special edition released in 2009, featuring updated graphics, full voice-over, a re-mastered musical score, and a new interface that eschews the SCUMM interface for a context aware mouse cursor. The voice-over and score were really nice, the updated graphics and interface… well, not so much.

The game includes a hot-key to swap between the two modes, but switching to the older graphics also removed the voice-over and remastered score. I started by playing in old school mode and switching over to the remastered mode for the interactions with other characters, mainly for the voice-over work, but that grew tiresome. Fortunately, thanks to the open nature of SCUMM, some dedicated fans made it possible to play the old version with all of the new audio. (I was not alone in my frustration apparently!) The fan-made Ultimate Talkie Edition proved to be the best way to play it, and I highly recommend it to anyone looking to play the game today.

As for the game itself, I loved it! The Secret of Monkey Island combined silly humor and flavorful puzzles into a melange that felt like custom made for my taste and sensibility. Like Maniac Mansion, there were a few puzzles that felt a little more esoteric than fair, but they showed up at a lower percentage than I expected and almost always made up for the difficulty by being inventive and entertaining. Additionally, as far as I could determine, there were no dead ends to be found. While the game lacks the replayability of Maniac Mansion, it was a huge leap ahead in both scope and narrative ambition and ranks as one of my favorite video game experiences of all time.

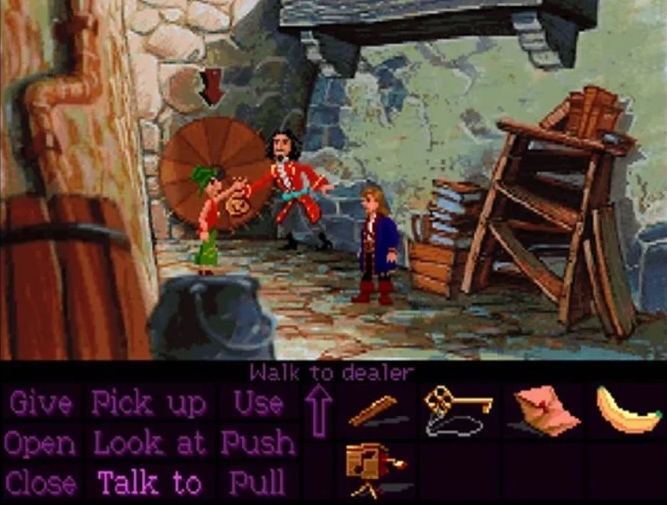

After finishing The Secret of Monkey Island, it was a delight to immediately be able to dive right back in with another similarly good gaming experience in Monkey Island 2: LeChuck’s Revenge. I played through the special edition released in the 2010, and, thankfully, the makers learned their lessons from first game’s Special Edition, allowing you to keep the new audio without having to keep the new graphics and control scheme. (Which were still not my cup of tea.)

While going from Maniac Mansion to Secret of Monkey Island was a giant leap forward, LeChuck’s Revenge is more of a side step. It’s a very good game, but the less linear nature of the game also pulled away some of the focus that made the first game so good. The game has more locations to explore, but instead of focusing the puzzles within each area, the pieces for each puzzle were often spread out across all of them. If you missed a small item on an island that you needed for a later puzzle, you might have to go back and scour all of the islands for something that you missed. I get easily frustrated when I find myself backtracking over and over and this game had a lot of that. (This might be why I’ve never really gotten into Metroidvania-style games as well.)

All that said, while I didn’t like LeChuck’s Revenge as much as the first game, it’s still a very good game and one that is worth playing, even today. The narrative shines, the jokes are really funny, and—while divisive to some—the unexpected ending of the game is really memorable. This game was clearly a labor of love for the creators and it shows.

I will give credit where it’s due to The Curse of Monkey Island, it definitely didn’t play it safe. While the skeleton of the game is the same as it predecessors—I’m pretty sure the whole thing runs off of puzzle dependency charts—the interface and visual style have been given a complete overhaul. The charming pixel art graphics of the first two games has been replaced by a charming cel-shaded graphic style. Gone are the verbs in the bottom left-hand corner, replaced by the context-sensitive mouse interactions. While I prefer the former, I have to admit that the Saturday morning cartoon style works well with the series’ slapstick humor and juvenile wit. It’s also the first Monkey Island game released on CD-ROM, allowing it to have voice acting, a better musical score, and animated cut scenes. It’s also, despite the simplified interface, the last Lucasarts Games adventure game to use the SCUMM engine.

This is the first game in the series without Ron Gilbert, Dave Grossman, or Tim Schafer’s hands in the mix and their absence is definitely felt. The puzzles were fine, but not great. The narrative and the jokes felt like they were looking back at the first two games and trying to recreate their vibe by committee. That said, there is one exception to everything I just said. By far the best part of the game, a new character that felt like he had been in the series since the beginning. I am referring, of course, to Murray, the talking skull. All hail Murray! I’m happy to have played through The Curse of Monkey Island once, but I think once was enough for this one.

I don’t have a lot to say about Escape from Monkey Island. I tried it, getting most of the way through the first act, but didn’t finish it. Gone is the SCUMM engine, replaced by clunky Playstation-era controls and graphics. Neither of which were an improvement. I might have had more patience for it if I hadn’t just played through three other, superior titles in the series, but I also don’t feel the need to go back and finish what I started here.

Even though I’m writing this in 2024, I actually played through all of the above games in the Fall of 2022. So it was both coincidental and convenient timing that a new Monkey Island game dropped less than a week after I gave up on Escape from Monkey Island. Though, I was worried that I might be a little burnt out on the series, so I waited a year before diving into this one. I’m glad I waited, because Return to Monkey Island is a return to form and rivals the first game in quality and I think coming in fresh was the best way to experience it.

While the game doesn’t fully return to its SCUMM roots and pixel art design like Thimbleweed Park did, it is the first modern interpretation of the Monkey Island aesthetic that I’ve really liked. It’s a charming, almost paper-craft like vibe that makes you feel like you’re playing through a story book. It feels distinctive to the series and compliments the game play on multiple levels. While there are disappointingly no verbs in the bottom left corner of the game2Leaving them out makes it easier to port to consoles, is the reason I’ve seen given for their absence, the context sensitive mouse pointer system works well.

Most importantly, the puzzles and the writing are uniformly excellent. The puzzles are still offbeat and challenging, but feel consistently fair, something the first two games would struggle with from time to time. Ron Gilbert and Dave Grossman are both back for this release and, being thirty years older than the last time they made a Monkey Island, have wisely adapted the narrative to reflect that. While The Secret of Monkey Island is about a young man looking to make his mark on the world, Return to Monkey Island features an older, more reflective Guybrush. It’s a choice that allowed the Ron and Dave to craft a story that is more personal their current experiences, and that’s a choice that’s almost always going to lead to a better story.

The game picks up from LeChuck’s Revenge‘s controversial ending and runs with it, mostly tossing out the events of Curse and Escape wholesale. (Though Murray, the talking skull, does appear—as he should!) The game revisits a lot of the locations and characters from those first two games, but avoids simply repeating what those games did, instead coming up with innovative new riffs on the old favorites while exploring new ideas, characters, and locations. I don’t know if there will be more Monkey Island games, but I do know that this game works as a perfect conclusion to the series. I’m looking forward to replaying The Secret of Monkey Island, LeChuck’s Revenge, and Return to Monkey Island in a few years— after I’ve forgotten enough to make the puzzles fun again—and re-experiencing the narrative arc.

There’s two diametrically opposed movements happening in video games right now. On one side, you have AAA publishers spending massive amounts of money to make massive, photorealistic video games that need to make an increasingly large amount of money in order to both pay for their development and to satisfy late-stage Capitalism’s desire for constant growth at any cost. That’s the direct evolution of the video game industry that created these adorable point-and-click games in the late 80’s and throughout the 90’s. In chasing that constant growth dragon, the point-and-click adventure genre was largely abandoned in the late 1990s and early 2000s, as it is a more niche genre with less potential for market share growth than a FPS that recreates WWII, an annual release in a Football franchise, or a Zombie survival game. (That’s not saying those games are necessarily bad, AAA games like Breath of the Wild, Baldur’s Gate 3, and The Last of Us are pretty great too!)

Thankfully, over the last decade, with the advent of digital publishing platforms like Steam and Xbox Arcade and crowdfunding platforms like Kickstarter, there’s been the rise of the other force in the industry, the independent game movement. Less concerned about profits, ARPU, and maximizing market share, the movement has allowed for niche games to be created that don’t have to be everything to everyone. You can have games like Stardew Valley, Return of the Obra Dinn, or Balatro come out of nowhere from one or two developers. They’ve proven that not everything has to be a ray-traced, 80-hour experience.

More germane to old-school, 2D point-and-click adventure games, I think it was the overwhelming success of Tim Schafer’s Double Fine Adventure Kickstarter (aka Broken Age) really opened a lot of eyes to the fact that that there’s still a demand for these type of games. Thanks to that we got Thimbleweed Park, which is likely what led to Return to Monkey Island getting made Even more importantly, it’s also led to a lot more point-and-click adventure games being made in general, many by small independent teams that likely wouldn’t have been able to make their games before the digital publishing and crowdfunding era. I’m really looking forward to playing more of them and I’m excited that I can do so having played through these formative SCUMM games that they are all building on the shoulders of.

Additional Reading

Obviously I didn’t go from not knowing that Thimbleweed Park was a homage to SCUMM games to knowing that The Curse of Monkey Island was Lucasarts last SCUMM game without doing some research. Here’s some of the articles that I read and found interesting:

- “A truly graphic adventure: the 25-year rise and fall of a beloved genre” by Richard Moss for Ars Technica

- ScummVM: https://scummvm.org

- Ron Gilbert’s Blog: https://grumpygamer.com/

- Maniac Mansion Fan Reference Site: http://www.maniacmansionfan.50webs.com/

- Monkey Island Fan Reference Site: https://scummbar.com

- Wikipedia Pages: